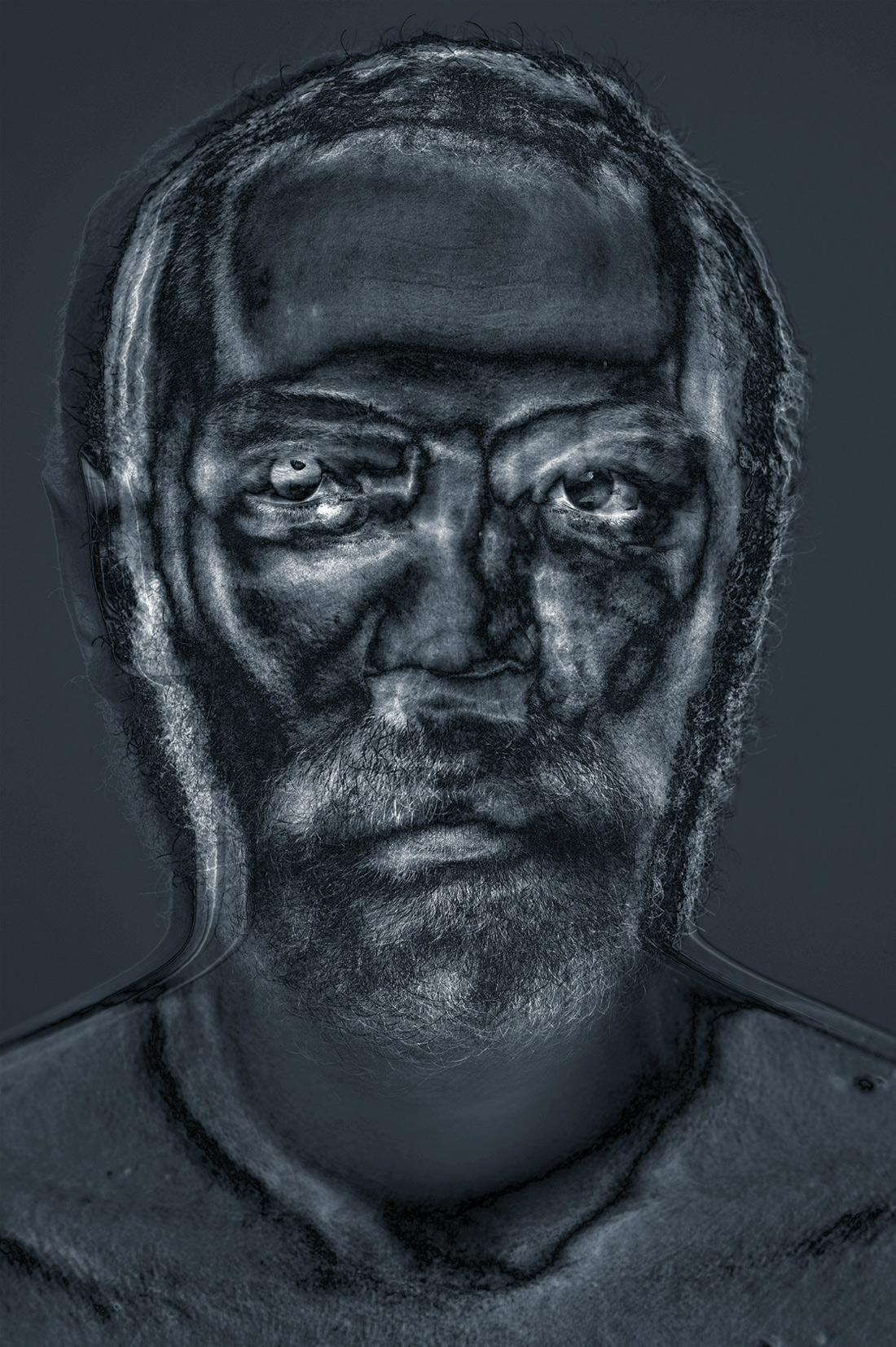

LA PRAIRIE INVITES: MILO KELLER

The American artist Ansel Adams once claimed that “there are two people in every picture: the photographer, and the viewer”. Today, we live in an age in which, via the advent of our smartphones and their plethora of instant editing technologies, we have all become both photographers and viewers of innumerable images. It is, as such, arguable that the true craftsmanship and artistic eye of the photographer has become somewhat threatened by the 21st century, clouded by the endless cavalcade of photographic images we both produce and consume on a daily basis.

How important it is then, that the aforementioned craft and artistry of photography remains nurtured, encouraged, and driven forward by certain centres of excellence, and spearheaded by those who are laying pathways for new generations of photographers to follow. The Ecole Cantonale d'Art de Lausanne (ECAL) is regularly proclaimed as one of the best art and design schools in the world, and with almost two hundred years of pioneering expertise as a powerful foundation on which to build, the school remains a beating heart of innovation and excellence for its field. La Prairie had the exclusive opportunity to speak with ECAL's Head of Photography, Milo Keller, and gain insight into his thoughts on the evolution of photography, and where the future of his craft may lie.

Keller’s life has been one in which cameras, lenses, and photographic film have always been present. Speaking of his love for photography, he is drawn, perhaps inevitably, to thoughts and memories of early childhood. Keller’s grandfather was an amateur photographer, who captured his travels throughout Asia and Africa on film. However, it was Keller’s father, an architect who shared the professor’s love for the impact of light and shade, who was his first mentor. At just six years old, the young Keller began experimenting with reflex cameras, and discovered that photography was the one form of expression which felt natural, and which allowed him to begin building a visual language which was entirely his own. This perhaps offers a clue as to why Keller went on to tirelessly foster new talent, and why he remains keen as ever to candidly discuss his visions for the future of his craft.

Architecture is clearly one of the most significant inspirations behind your work, and something which continues to inform your output. In your mind, how do photography and architecture mutually influence one another?

Before even the invention of film, architectural designers were busily generating images. They may not have been photography, but in many senses, they were the origins of something which would eventually lead to photography as we know it today. In both photography and architecture, we are always focused on and always dealing with concepts of both light and space. Defining the darkness, illuminating space, and pinning down the essence and meaning of light sits at the very crux of so much of what we do. Once we determine where they can be found, the interplay between these universalities creates that all-important sense of three-dimensionality.

As we look back through the origins and the invention of photography, we invariably arrive at the camera obscura, the genesis of the media reliant on the architectural space. Through the camera obscura and other such methods, both architecture and photography arose and deepened side by side.

It could be said that at its core, the etymology of photography involves writing in light. As such, both worlds are connected to and bridged by this immaterial element.

Photography has been greatly influenced by new advancements in technology, not only today, but consistently throughout its history as an art and a craft. How do you feel technological advancements have added to photography, and do you believe, as many do, that it has taken something away from photography as a form of artistic expression?

Photography, of course, began with science, with the invention of the Daguerreotype and the innovations apparent in the early art of the 19th century. Since its inception, the craft of photography has been plagued by a tireless back-and-forth between technology and creativity. The problem, it seems, centered around the legitimacy of photography as a fine art. Early technology related to photo-making as an applied art; that is, an artform which was in service to something or someone. However, it’s also vital to keep in mind that this period of history was also marked by the production of incredible works of photography, many of which are found in fine art museums today, where they continue to inspire and amaze.

In more recent years, we have cultivated an intimate relationship between technology and photography, and the same back-and-forth remains constant and consistently present. Technologies now grow side-by-side with photography, and this continues to open doors and provide new pathways to explore. In essence, to make photography today is to seek the creative potential into new forms of image production. As any artist will tell you, this remains an unending search, and yet, this also remains a factor which makes photography both very exciting, and keeps it at the cutting edge of contemporary art.

So, when speaking about how we bridge the gap between the immediacy of new technologies and a long-appreciated craft, you feel that the gap itself is a key aspect in what makes photography compelling?

Yes, this is something I have worked on extensively across my career. Here at ECAL, we proudly remain an applied art school. In fact, we are particularly fond of this term; it allows us to switch between fine to an applied art, and it gives the students freedom to move back and forth as well. This flexible approach allows us to teach them almost everything and explore different avenues of the same consistent vision.

We begin with the history of the medium and linking analogic black and white photography to the future of art as a whole. Students learn how to use small, medium, and larger-form cameras, and even recreate images in styles borrowed from the 19th century. It’s endlessly fascinating to see how certain techniques lend themselves to certain styles, and how the past in photography never fails to offer so much to the present.

We teach our students how to develop black-and-white themes, how to print, and how to work in a dark room. However, at the same time, we also instruct our students in how to use digital cameras, how to use multiple software, and experiment with virtual reality and all relatively new technologies which were not long ago at the very cutting edge of photography and image making, but which we are all increasingly familiar with. These groundbreaking techniques are already prevalent in commercial activity, and yet they are also gradually coming into the fine art world, and helping new artists establish their visual language. So, it is truly a form of acrobatic teaching, contingent on diverse specialists from across the field.

As a professor, have you noticed any significant differences between the stylistic approaches of up-and-coming photography students, in comparison to more established photographers?

Absolutely yes. There is no getting away from the fact that, although all of the professors at ECAL have a deep and profound knowledge in their respective fields, we learn so very much from our students. As digital natives, they have grown up with the internet, with video games, and mobile devices at their fingertips, and as such they have a familiarity and capability with such devices which allows them to explore several platforms at once. This immediately lends itself to the creation of whole new aesthetics, which are immersed fully in a digital culture which is entirely their own.

Why is it so important to foster young talent today, and how does ECAL support their students during and after their academic studies?

During the academic curriculum, we do not just invite external guests to ECAL, we also regularly collaborate with brands and with magazines. This fosters an awareness of business practice, especially in knowing how to deal and speak with future clients and customers. At the very same time, we pair with important cultural institutions, including C/O Berlin, Foam in Amsterdam, Festival Images Vevey. Seasoned curators are also here quite regularly, working on portfolio reviews at ECAL.

Together, with the new Master Photography program, we do partake in research projects involving cutting-edge technologies, inviting practitioners and scholars who work together searching for creative potential in the new contemporary photography techniques. We have completed a first research project called Augmented Photography which has allowed us to give a strong identity to the Master Photography.

In addition, we benefit from extensive travel opportunities, and have been fortunate enough to take the students to Rio de Janeiro, Cuba, New York, and soon, to Tokyo. Major annual photography events, such as Paris Photo in November and Photo London in May are part of our academic calendar, and we often find ourselves organizing exhibitions during the fairs. At these particular times of the year, we aim to reconnect current students with alumni as we spend time together celebrating photography

What do you hope to see in the future of photography?

It is my sincerest hope and wish that my students will become a part of the future, not merely the future of photography, but of photographic images and all that this entails. As we have moved into the 21st century, it has become clear that the future of our teaching, our students, and our approach overall should move beyond traditional photography, and into a realm which challenges the connection between the art and applied forms. This means seamlessly transitioning from CGI worlds (Computer Generated Imagery), made of virtual landscapes to reality. I envision photography losing its constraint in traditional automatic approaches, and instead embracing tradition alongside more progressive and groundbreaking views. I’m confident this will come to pass one way or another. I continue to see inspiring, encouraging exhibitions and options which fully support this vision, and the future of photography is rolling out before us in unstoppable and deeply inspiring ways.

Finally, if you were able to take your thoughts, feelings, and instincts regarding photography, and distill it to one piece of advice to offer emerging creative talents, what would that advice be?

It’s very simple: Be yourself. Do not pause too long to mull over what clients wish to see, do not ponder or struggle with thoughts of cultural institutions. First and foremost, think about something for yourself, attempt to explore yourself, and create that visual language all artists have within themselves. Embrace and explore your native creativity, construct your own artistic vocabulary and allow it to manifest in your own voice. After all, if you try to do something for others, then you are always in danger of losing your specificity and your interest. The answer is quite definitive: find your own way of seeing.