THE PERFECT ENCOUNTER

Since the dawn of time, humanity has sought answers to the secrets of the universe through its most mystical channels: the charm of art and the discovery of science. Together, their overlap creates a pathway to understanding what captivates us across fields, holding the ultimate key to truly understanding the power of beauty. By dazzling with aesthetics and educating with science, these mysteries can truly be revealed. Those who are curious and passionate can find joy in both subjects; through calculation and expression, both schools of thoughts experiment, then align to provide us with the foundation to illuminate what has thus far remained a mystery. Art is the way we display that newfound knowledge.

Since Ancient Greece, the linguistic overlap between technique and technology has dictated the evolution of art as a tool: Technê τέχνη is translated both as art or craft and as the root of "technology". The linguistic subtlety mirrored the development of art as a skill, as pottery, sculpture, and other artisanal building blocks of pigment and color theory, which all paved the way for antiquity’s masterpieces. As art also became two-dimensional, the significance of linear and geometric formulas leveraged science for paintings, drawings, and the art of modernity.

The Renaissance was defined by an all-encompassing curiosity. In 15th-century Europe, discovery and creativity went hand-in-hand as intellectuals strove to develop answers to questions in medicine and music, art and arithmetic. In order to find these solutions, artistic intuition paired with observational mastery. This unification of thought was a guiding force during this pivotal era and served to set the stage for critical thinking throughout history.

To this end, art has always been influenced by science. Both the science and art of today began in the Renaissance, culminating with Leonardo da Vinci’s insatiable quest to challenge the universe’s largest, unanswerable questions. A keen observer of the world around him, he applied this fascination to the works he created. As Walter Isaacson’s authoritative biography explained, his extraordinary curiosity made science his true passion. Around gravity and human nature, it was love affair bordering on obsession. He gathered copious notes on the motions and sounds of machines and mammals, even the inner-workings of childbirth, and discovered breakthroughs in aviation, music, and medicine that would not be developed for centuries to come, even predating Galileo by more than a century. Da Vinci was constantly experimenting and theorising, looking for patterns in the rhythm of life.

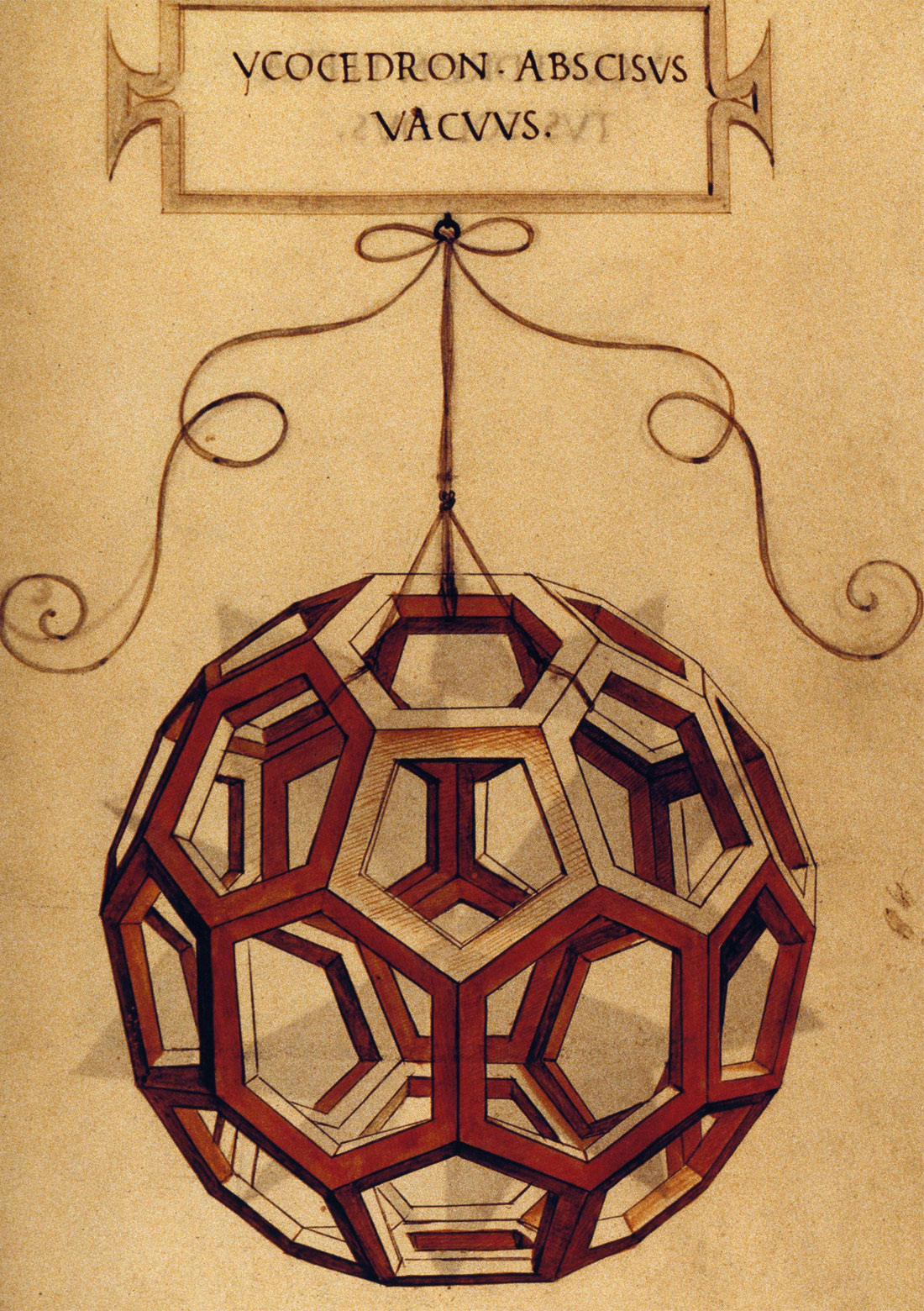

This interconnectedness across art, science, and inevitably, humanity allowed his portraits to truly capture the essence of his models, seeing the world within the individual. His ever-inquisitive mind led him to partner with mathematician Luca Pacioli for their patron Duke Ludovico Sforza in Milan. An early accountant and a frontrunner in what is now known as double-entry bookkeeping, Pacioli taught Leonardo da Vinci mathematics, and had a significant impact in the artist’s understanding of proportion and symmetry. This partnership resulted in Divina Proportione (the Divine Proportion), a book developing the idea of perfect proportions in art through scientific drawings and sketches designed by da Vinci himself.

This duplicity drives viewers to delight in his work, and is synonymous with the Renaissance value of curiosity. Because he thought differently and saw the connivance between art and science, his genius continues to be esteemed and echoed into modern day.

Helen Birch Bartlett Memorial Collection, 1926.224.© 2019.

Photo: ©The Art Institute of Chicago / Art Resource, NY/ Scala, Florence.

Cross-categorical thought processes fostered in the Renaissance were pushed forward into modernity, eventually leading to the late 19th century’s groundbreaking accessibility in art. With the developments of chemistry, artists had access to new materials on daily basis, opening a whole new world of opportunities to experimentation with different techniques. At the same time, scientists tried to explain just about everything with mathematical formulas. For a while, it looked like everything would become explainable, including people’s feelings when exposed to art.

When Georges Seurat developed his interest in colour theory in the 19th century, the result was simple yet revolutionary. During his lifetime, scientists had demonstrated how the human eye perceives a colour in relation to its surroundings. It was then thought that mixing red and blue to form a purple pigment was becoming unnecessary as the same effect could indeed be achieved with dots in those same colors, only displayed side by side. Georges Seurat believed this dotted purple to be more energetic and vibrant than mixed pigments, as the colour was then created in the mind of anyone who would peer down into his paintings. While this science later ultimately proved false, Georges Seurat’s paintings possessed a special charm, in which the space between his dots created light to filter through the canvas. The technique came to be known as Pointilism—from dots—although it was more accurately Divisionism, the division of colour, while Georges Seurat referred to his work as Chromoluminarism. Regardless of the labels it bore, this style markedly defined outlasting movements, in its characterization of electrifying new colors, daring techniques, and a clear innovative vision.

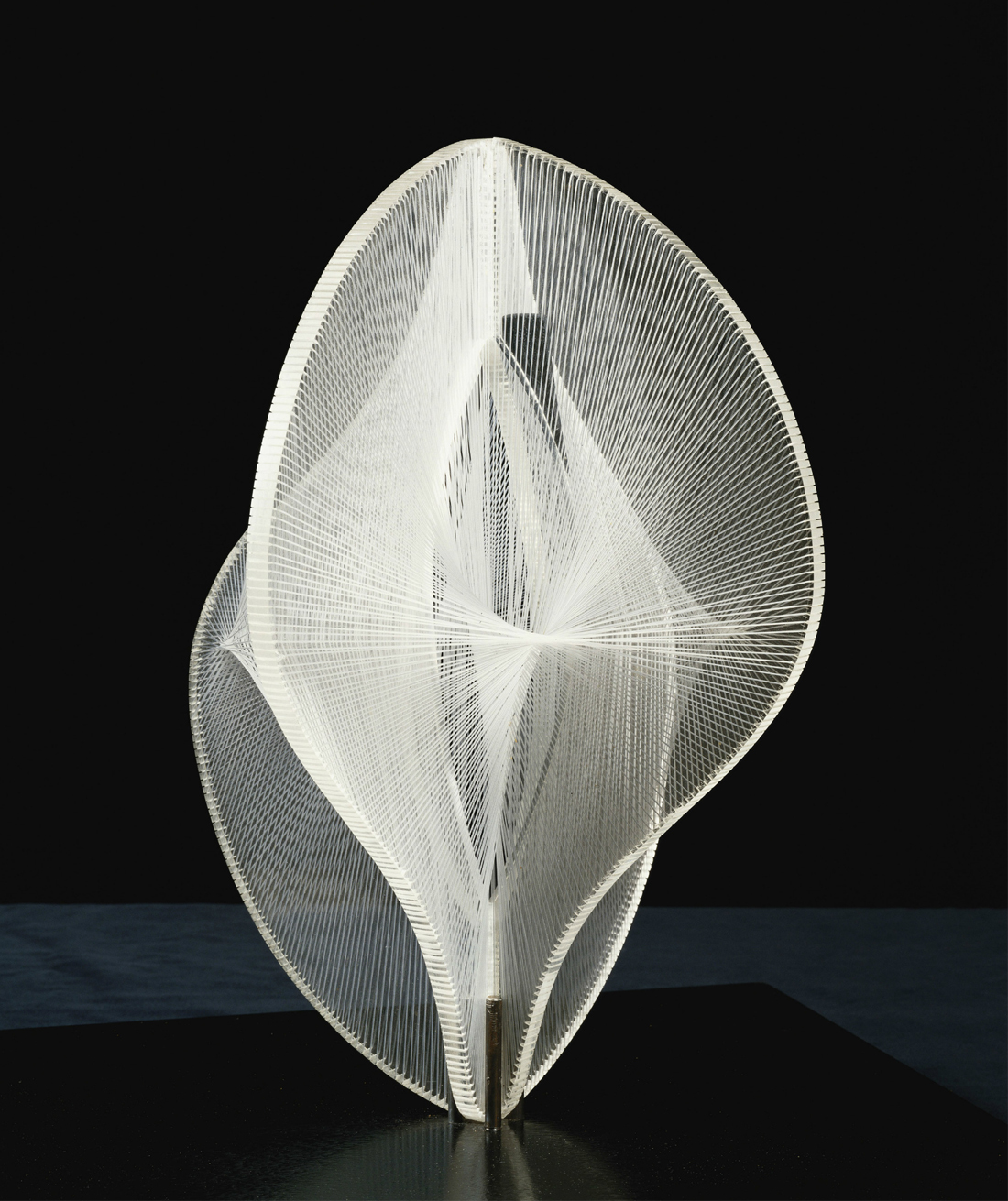

Building on the advances of 20th century painting, advances in 21st century technology allowed the artworks themselves to become mobile. The work of Alexander Calder and Naum Gabo took the energetic shapes from the canvas to sculpture, distilling them into abstraction.

One strong example of this is Linear Construction in Space No.2. Naum Gabo leveraged the discourse on the growing power of revolutionary ideas in his early life to create moveable sculpture, illuminating the tectonics of change. This work was made in twenty iterations, with nylon fibers catching the light as they shift. The many evolutions have been displayed in the most renowned museums around the world, setting the stage for kinetic interactive art of the future.

Alexander Calder also understood the value of motion, coalescing with the Arts and Crafts movement of California to build on tool-making and creation. Developing scientifically powerful kinetic sculpture relied on a methodical system to test various styles of movement, ultimately allowing for a successful result to come alive.

Photo: ©Christie's Images, London/Scala, Florence.

For contemporary artists, today’s ever-evolving stream of scientific developments represent a bottomless source of inspiration, allowing for original works of art that would have been thought to be impossible only a few decades ago. The previously unimaginable or at least inconceivable works are now being made a reality through the creation art objects challenging both the mind and the body, going beyond human limitations.

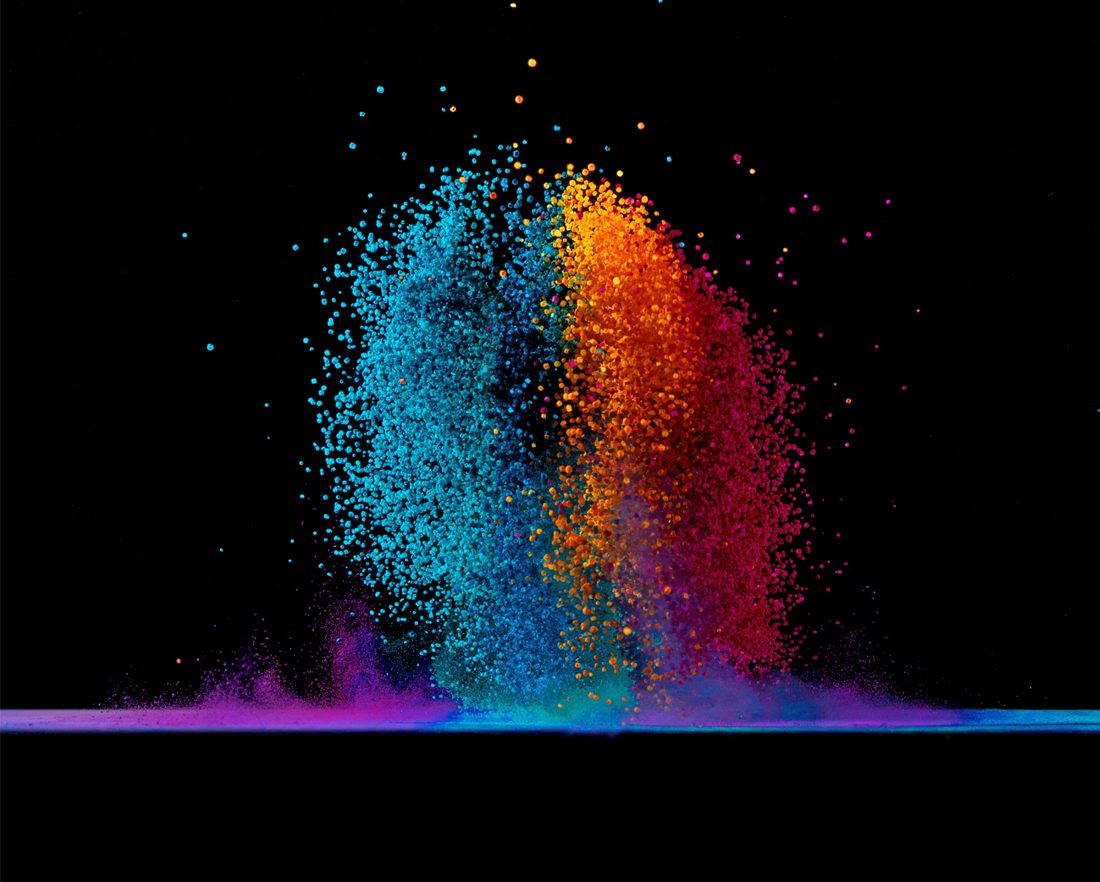

Artist Fabian Oefner offers to visualise sound. Seeking to turn soundwaves into visual works of art, he focuses on the movement of sound to bring it to life. By affixing thin plastic foil with small crystals on a loud speaker, he allows for the motion to dictate the artistic result. With the sound, the crystals come alive, in a vibrant and ever changing picture.

One exceptional harness of the power of science is LIVING CELLS by Paul Coudamy. Produced in collaboration with La Prairie for the 2017 edition of Art Basel in Basel, the geometric structure of lacquered steel and magnets has been precisely defined according to the mathematical formula known as Weaire-Phelan. The construction of LIVING CELLS began with modeling each bead and its spatial assembly. These forms were cut in steel using lasers and digital folding following a numbered pattern, then hand-welded to build the structure. Shiny black magnetised marbles – reminiscent of caviar – appear to colonise the structure in clusters, spreading out like a living entity over a static skeleton. The overall volume is in constant flux, as the magnetic tensions of the marbles are forever creating new, unique forms. As the artist explained, “the concept of LIVING CELLS is to bring a confrontation between nature, geometry and science.”

In the digital age of the 21st century, the intersection between art and the Internet is not just inevitable, but increasingly prevalent. The impact of the Internet on the creation of digital art continues to grow, with a number of artists, known as algorists, co-creating with computers through Internet platforms and algorithms, qualified as algorithmic art. Relying on the computer algorithm to generate its design, it came to fruition following a conference in 1995, although fractal artwork in the 1980s, computer-inspired art in the 1960s, and even Oriental tile patterns bear similarities to this innovative movement. Often showcased on a computer screen, algorithmic works of arts offer a meta-analysis of their own form, using the same mechanism for creation and display.

Founding algorist Jean-Pierre Hebert was at the forefront of this movement, using sand and other temporal materials in the mid-90s, spreadsheets and datasets function in place of paint and canvas. Engagement data gathered from surveys or consumers behavior is subsequently transferred using sophisticated mining software, relied on by scientists and journalists alike. These methodologies speak to the 21st century changing world of analytics, fostering a modern personal expression. Through robotics and data visualisations as art, human truth is revealed.

One such groundbreaking artist is Refik Anadol, whose ‘Melting Memories’ work syncs brain scans of donated memories to his computer for visual representation. The result is staggering—the memory is constantly shifting and realigning, coming alive binding human behavior and scientific connection.

In many ways, the algorithmic work of the 21st century has its roots in Renaissance questions. Who are we? Why do we matter? As the untold stories of the universe are revealed through science, they are fleshed out through art. This mutual relationship of art and science is the result of strong influence, an outstanding synergy that has been creating beauty by visualising philological questions on the edges of our understanding of reality. The poetry of the unknown is served through these influences, allowing our questions to slowly find answers in their exquisite uncertainty.

Science or art?

This is a question that invariably arises when discussing the life and work of artists throughout the ages. Such figures often laboured in a world where science and art lived side by side – a fusion of precision and poetry, of research and creativity, and of quest and achievement.

In pursuing the quest to offer timeless beauty, La Prairie sought to find a way to prolong and compound the outstanding lifting and firming benefits offered by the Skin Caviar Collection. Through an artistic and innovative approach to complexion enhancement products, La Prairie has taken caviar science to new heights, fusing it with exquisitely textured foundations and powders.

Inspired by this alliance of art and science, La Prairie has created an environment of expertise and savoir-faire, where a fusion of caviar science and colour artistry takes place. It is where fusion lives, and it is where the Skin Caviar Complexion Collection comes to life.